Engineering LLM-Based Agentic Systems

Image from Practical Considerations for Agentic LLM Systems

Part of our ongoing exploration into the latest trends in ML engineering best practices we identified five key areas that define the current landscape. This article delves into the third area: Agentic systems, and marks the third part in a series dedicated to examining recent advancements in ML engineering, highlighting emerging challenges, and discussing under-represented topics.

Our analysis shows that LLM-based agentic systems form a new class of autonomous systems, emulating traditional agent capabilities through language-based reasoning, planning, memory, and tool use. Unlike more traditional multi-agent architectures, their context-sensitive and stochastic behavior poses challenges for reliability, coordination, evaluation, and trustworthiness. We highlight key design patterns and engineering strategies that help address LLM limitations, alongside emerging approaches to semantic interoperability, such as the Model Context Protocol. These insights offer a view of current practices and open challenges for engineering agentic LLM systems.

Definition and Taxonomy

Developing clear definitions and taxonomies for the emerging class of agentic systems is a notable area of study [74, 1n]. The academic definition of agency, developed through research in multi-agent systems, provides a conceptual foundation for analyzing LLM-based agents. Traditional agent theory characterizes autonomous systems through four capabilities – belief representation, reasoning, planning, and control – typically implemented as heterogeneous subsystems such as knowledge bases, probabilistic or symbolic planners, formal logic engines, etc.

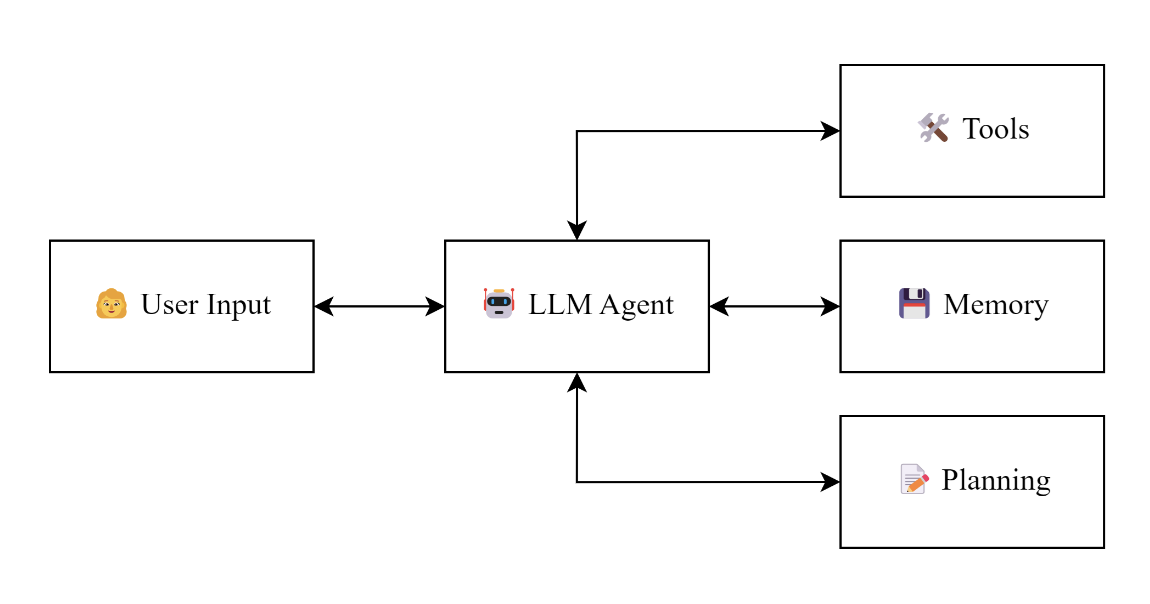

Contemporary LLM-based systems – built upon large pre-trained generative foundation models – seek to emulate this architecture via the orchestration of four analogous modules: reasoning, planning, memory, and tool use.

Yet, despite this structural resemblance, traditional agent architectures realize these capabilities through computationally specialized components, whereas LLM-based systems implement most functions within a single pre-trained model, modulated through prompt engineering and role-based conditioning. This motivated a distinct taxonomy – referring to such configurations as LLM-based agentic systems rather than agents.

Furthermore, the underlying objectives and principles of traditional multi-agent and LLM-based agentic systems are distinct. In the more traditional research, agents are modeled as autonomous decision-makers situated within an environment with explicitly defined goals, utility functions, and interaction protocols. Their collective dynamics are analyzed in terms of coordination, cooperation, competition, and equilibrium-seeking behavior.

In contrast, LLM-based agentic systems do not operate under explicit utility functions or equilibrium-driven objectives. They are language-conditioned, goal-directed generators that approximate agency through context-sensitive inference and generative modeling.

Their behavior emerges from the statistical regularities encoded in large-scale pre-training, rather than from explicit optimization over well-defined reward landscapes. Coordination or “multi-agent” interaction in such systems is therefore emergent and representational, rather than formal and algorithmic – a byproduct of shared linguistic priors rather than equilibrium-seeking dynamics.

This shift introduces new architectural and orchestration challenges, as coordination among multiple LLM-based agents lacks explicit objective functions, making it difficult to determine task completion or success. As a result, their collective behavior is less predictable, often heterogeneous across instances, and sensitive to variations in prompt design, context, and interaction history. Determining whether a coordinated outcome satisfies an intended objective becomes an interpretive rather than computational task, complicating both the design and assessment of agentic systems.

Patterns and architectures

Several architectural patterns and reference architectures emerge. For example, [44, 77] proposes a set of 18 architectural patterns that offer systematic guidance for designing and implementing LLM-based agentic systems. These patterns can be broardly organized into four functional architectural layers:

-

Goal Understanding & Prompt Management – or the input interpretation layer – translates natural language intent into structured, actionable directives through prompt engineering, query reformulation, and contextual grounding techniques.

-

Planning & Reasoning – or the strategic orchestration layer – decomposes high-level objectives into executable action plans using reasoning paradigms such as one-shot inference, chain-of-thought prompting, and iterative model interrogation.

-

Reflection & Improvement – or the quality assurance layer – enhances reliability and consistency through self-critique, cross-agent validation, and iterative refinement mechanisms.

-

Tools & Governance – or the operational infrastructure layer – supports system-level integration via external tool invocation, resource coordination, compliance enforcement (e.g., safety guardrails), evaluation protocols, and API orchestration.

This layered architecture aims to address the challenges discussed above, such as goal ambiguity and outcome indeterminacy. For example, the first layer mitigates the absence of explicit objective functions by translating open-ended language inputs into structured representations of intent. Similarly, the third layer partially compensates for the lack of formal success criteria through iterative reflection, evaluation, and self-correction.

Complementary design patterns identified in related literature [2n, 3n] address similar architectural concerns, including: (i) Reflection – enabling self-assessment and iterative performance improvement; (ii) Planning – facilitating systematic task decomposition; (iii) Tool use – extending capabilities through external resource access; and (iv) Multi-agent collaboration – supporting role specialization and cooperative problem-solving.

Fundamentally, these patterns seek to mitigate structural limitations of current LLM-based systems and use coordinated orchestration of agentic modules playing different roles to transform otherwise monolithic models into more modular, adaptive, and goal-directed systems.

Responsible development of agentic systems

Outcome indeterminacy also extends to the assessment of trustworthiness in agentic systems. To improve transparency and accountability, recent approaches propose the integration of dedicated verification agents and Responsible AI (RAI) plugins that can enforce ethical principles. Such mechanisms can include continuous risk assessors for real-time monitoring, black-box recorders for auditable traceability, and adaptive guardrails that mediate interactions between the agentic systems and the external environment [4n,8n,9n,10n].

Guardrails emerge as the more scalable and modular approach for agentic RAI [56] – serving as control layers that regulate inputs, outputs, and intermediary processes to ensure compliance with ethical, legal, and user-defined requirements. These may be implemented through (i) RAI knowledge bases composed of curated rules and policies, (ii) narrow models trained for specific safety or compliance tasks, or (iii) RAI-augmented foundation models dynamically linked to RAI knowledge sources during inference.

A comprehensive guardrail framework typically spans six complementary types across the agent’s operational lifecycle:

-

Input guardrails – sanitize user prompts (e.g., anonymization).

-

Output guardrails – filter generated content to prevent harm or non-compliance.

-

RAG guardrails validate – retrieved data for quality and relevance.

-

Execution guardrails – control tool or model invocation through permission lists.

-

Intermediate guardrails – validate workflow steps and manage fallback behavior.

-

Multimodal guardrails – extend oversight across text, image, and UI channels, ensuring accessibility and design compliance.

Taken together, these mechanisms aim to build a layered assurance architecture that embeds continuous verification and adaptive oversight into agentic workflows.

Reliability and Deployment:

Further challenges in reliability and consistency in deploying agentic systems follow from the challenges discussed above. For example, minor changes to the underlying model – such as upgrading to a newer checkpoint or modifying sampling parameters – can yield significant variations in reasoning, planning, or output structure. These inconsistencies can propagate through downstream components, undermining the overall robustness and user trust of systems built around agentic LLMs [20, 54].

To address these limitations, deployment environments that demand task consistency and predictable behavior may combine traditional engineering with adaptive LLM orchestration. Two broad mitigation strategies emerge as effective. The first involves manual plan definitions, in which humans define explicit task structures, role assignments, and prompt templates. This approach constrains model behavior within operational boundaries. The second relies on external planning augmentation, where the LLM is coupled with deterministic planners or reasoning modules [25]. In both cases, embedding traditional software components and plugins ensures reliability.

Deterministic subsystems handle core logic, validation, and control flow, while stochastic LLM reasoning is confined to domains where flexibility and creative generalization are advantageous. This design principle was formulated as the offloading of deterministic requirements to traditional software engineering [4n]. Rather than depending on the stochasticity of LLMs, more critical functionality – such as context tracking, constraint enforcement, or output validation – can be implemented through conventional mechanisms. Automated context management systems can guarantee that correct information is supplied to the model, while post-processing pipelines can standardize and verify generated outputs.

Nevertheless, stochasticity can also be leveraged as a resource. Because LLM outputs vary across samples, static retry mechanisms can exploit this variance: when an initial generation fails or is suboptimal, re-querying with the same or slightly modified prompt can produce superior results. To harness this effect safely, retry loops must be bounded, temperature variation can be introduced across attempts, and retry outcomes should be logged for empirical optimization. This transforms randomness into a more controlled form of diversity that improves average task performance.

Complementing these measures, short-circuiting strategies improve both efficiency and reliability by constraining unnecessary computation. Agents can be designed to terminate reasoning as soon as a correct or sufficient answer is available, guided by explicit stopping criteria which can be checked with traditional software engineering components. For simple or well-structured tasks, single-turn optimization enables agents to produce final outputs without redundant intermediate steps. Early termination signals can further prevent over-reliance on external tools or excessive reasoning loops, reducing system latency and error propagation.

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of these strategies remains application- and context-dependent. Their design often requires calibration, and broader practices or patterns have yet to crystallize as the field continues to evolve.

Interoperability and Model Context Protocol (MCP)

As LLM-based agentic systems are text-based consumers and producers, enabling text-based interoperability between these systems and external tools has become a design challenge. To address this, the Model Context Protocol (MCP) was introduced as an open, evolving standard for structured communication among LLM-based components and external resources [5n, 6n]. MCP defines common primitives for context sharing, tool invocation, and resource access, focusing on textual and semantic descriptions over more formal interface specifications, as developed in existing paradigms such as REST or RPC.

From this perspective, MCP aims to be an abstraction layer above existing communication protocols and execution frameworks, aiming to decouple agentic logic from resource implementation. In practice, this allows an agent to retrieve data or invoke tools through MCP-compatible interfaces without depending on a specific API or infrastructure standard (which is abstracted in the MCP implementation), and focusing on the textual description of the resources. The broader objective is to foster a shared ecosystem of interoperable, MCP-compliant tools and data sources, aiming to reduce reliance on proprietary integrations.

Nevertheless, MCP remains in its initial stages [7n]. While conceptually interesting, it currently lacks the maturity and consistency required for deployment in large-scale or enterprise settings. Core functionalities such as authentication, authorization, error handling, and state management still require task-specific implementations, as MCP focuses primarily on interaction semantics.

From this perspective, MCP can be seen as an initial move toward semantic interoperability, facilitating language-driven interactions across heterogeneous tools and systems. However, it remains an open question whether such interoperability is essential, or primarily a strategy to mitigate certain limitations of LLMs – such as their limitation to consistently and reliably execute API calls or manage structured external resources.

Conclusions

LLM-based agentic systems represent a novel class of autonomous systems, emulating more traditional agent capabilities through language-conditioned reasoning, planning, and tool use. Unlike more traditional multi-agent architectures, their behavior is context-sensitive, and stochastic, creating challenges for reliability, coordination, and outcome evaluation.

Consequently, the research in engineering LLM-based agentic systems focuses on addressing inherent limitations of LLMs, including goal ambiguity, inconsistent reasoning, outcome indeterminacy, incomplete task coverage, and unpredictable tool interactions. Layered architectures, modular orchestration, and mechanisms such as reflection, guardrails, and verification agents help mitigate these issues, while frameworks like the Model Context Protocol aim to support semantic interoperability with external tools.

Despite these advances, critical challenges remain – such as achieving consistent task performance, ensuring trustworthiness, and standardizing integration – underscoring the need for ongoing research into best practices, responsible design, and comprehensive evaluation frameworks for developing and deploying LLM-based agentic systems.

Notes

The reference notation is based on the references available in this article, complemented by new references that are marked with the n subscript.

New references

1n. AI agents vs. agentic ai: A conceptual taxonomy, applications and challenges

2n. Agentic Design Patterns

3n. The Agentic AI Mindset – A Practitioner’s Guide to Architectures, Patterns, and Future Directions for Autonomy and Automation

4n. Practical Considerations for Agentic LLM Systems

5n. https://modelcontextprotocol.io/docs/getting-started/intro

6n. A survey on model context protocol: Architecture, state-of-the-art, challenges and future directions

7n. Model context protocol (mcp): Landscape, security threats, and future research directions

8n. Trism for agentic ai: A review of trust, risk, and security management in llm-based agentic multi-agent systems

9n. Responsible Agentic Reasoning and AI Agents: A Critical Survey

10n. Inherent and emergent liability issues in llm-based agentic systems: a principal-agent perspective